Labelling preferences for medicines

Pharmac wants to outline for suppliers the naming and labelling preferences it has when considering a pharmaceutical for listing in the Pharmaceutical Schedule.

On this page

Legislation relating to the labelling of pharmaceuticals

The following legislation currently governs the labelling of pharmaceuticals (medicines, including controlled drugs used as medicines) and related products supplied in New Zealand:

- Medicines Act 1981

- Medicines Regulations 1984

- Misuse of Drugs Regulations 1977

Medsafe(external link) is the New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. It is responsible for the regulation of medicines and medical devices in New Zealand. Pharmaceutical labelling must comply with the “Guideline on the Regulation of Therapeutic Products in New Zealand: Part 5: Labelling of Medicines and Related Products [PDF](external link)”.

1. International non-proprietary names (INNs)

Particular care must be taken when designing a pharmaceutical name. Failure to do so can lead to communication and selection error which could cause harm.

Pharmac supports the World Health Organization’s initiative to protect INNs.

The use of the INN should be in accordance with the WHO INN guidance(external link).

1.1. Pharmac prefers that proprietary (trade) names for pharmaceuticals are not derived from INNs (generic names).

1.2. Where the trade name is the INN name in combination with the company name as an identifier, PHARMAC prefers:

1.2.1. The company name to be written in full to avoid confusion with formulation type. For example, ’ibuprofencompanyx’ not ‘ibuprofen-com’

It is expected that with two exceptions (adrenaline and noradrenaline), the INN will be used on medicine labels in the New Zealand market. Pharmac recommends the New Zealand Universal List of Medicines (NZULM)(external link) be consulted when designing a pharmaceutical name.

2. Umbrella naming

An umbrella segment is a section of a trade name that is used in the name of more than one pharmaceutical to create a brand for a range of products.

2.1. Pharmac prefers that suppliers develop trade names or use the full INN name. Pharmac recommends suppliers familiarise themselves with the approach taken by Medsafe outlined in its guideline.

3. Essential information

This is the information essential for the safe use of the pharmaceutical. The National Patient Safety Agency (England and Wales) has provided a series of useful design examples.

3.1 Pharmaceutical name

The name of the pharmaceutical should include both the generic name and the trade name (where applicable).

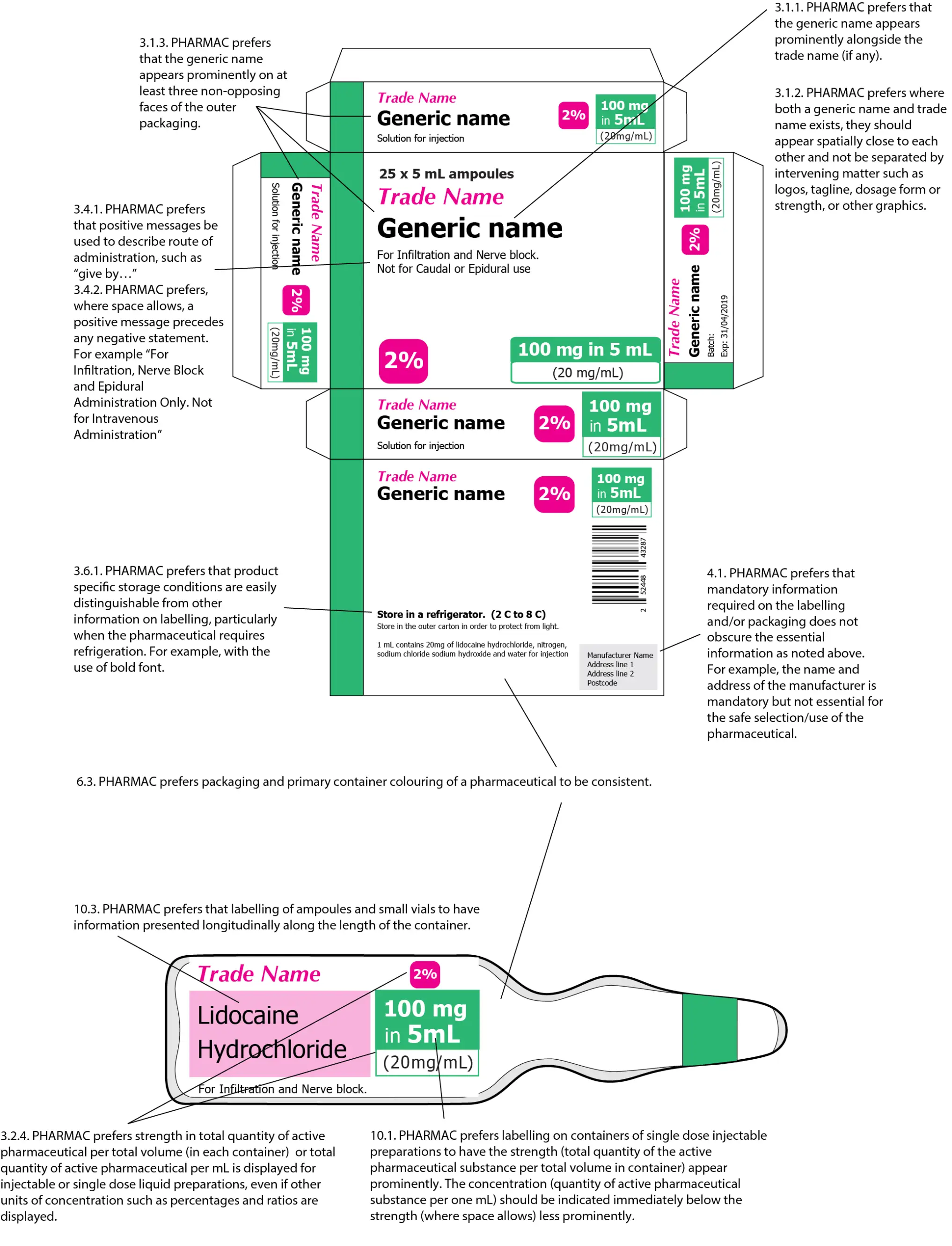

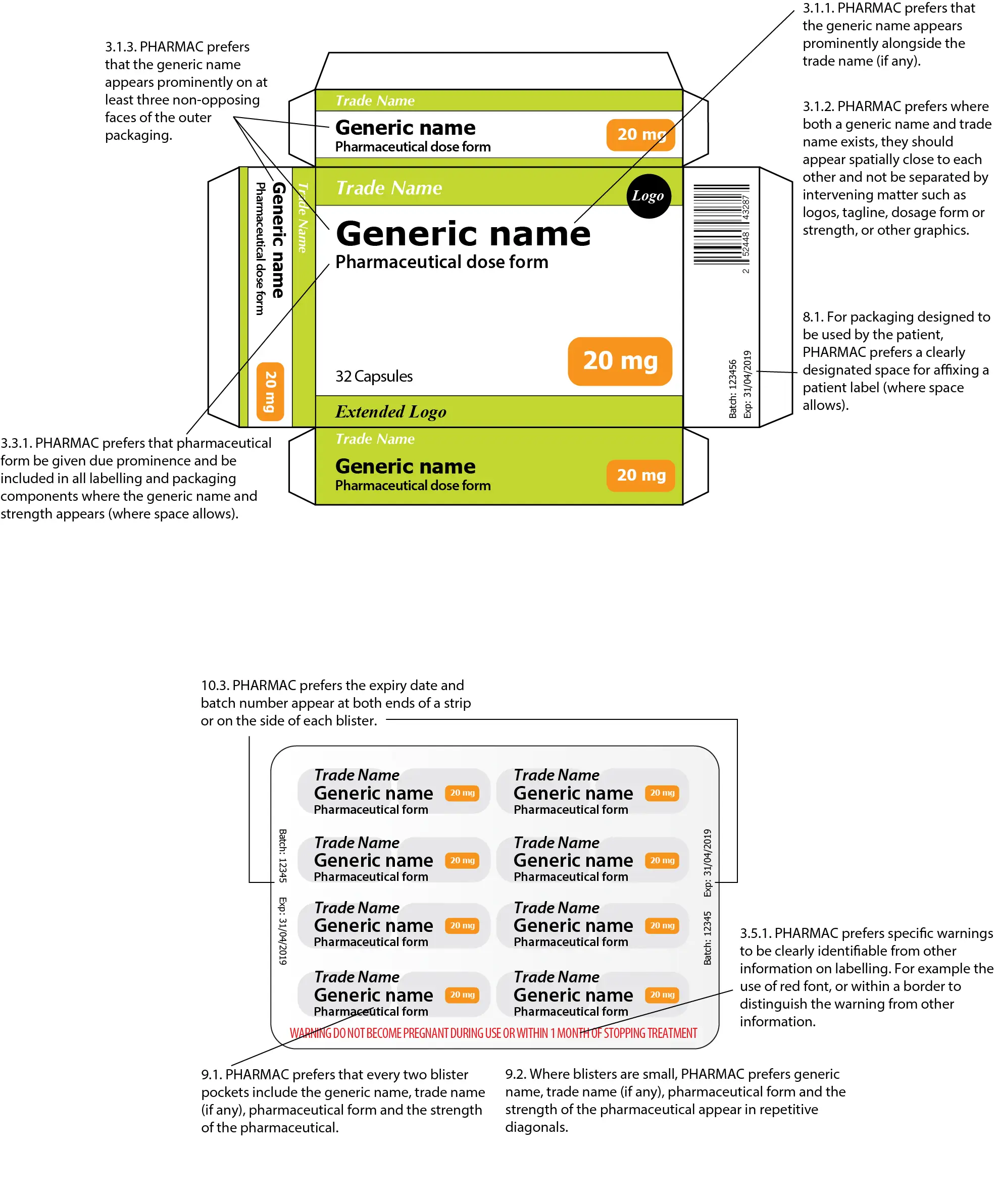

3.1.1. Pharmac prefers that the generic name appears prominently alongside the trade name (if any). See examples in figures below.

3.1.2. Pharmac prefers where both a generic name and trade name exists, they should appear spatially close to each other and not be separated by intervening matter such as logos, tagline, dosage form or strength, or other graphics. See examples in figures below.

3.1.3. Pharmac prefers that the generic name appears prominently on at least three non-opposing faces of the outer packaging. See examples in figures below.

Other design features such as the use of ‘Tall Man lettering’ can be utilised to further distinguish between different pharmaceuticals.

3.2. Pharmaceutical dose/strength/concentration

3.2.1. Pharmac prefers that dose strength be given due prominence and be included in all labelling and packaging components where the generic name appears.

3.2.2. Pharmac prefers that on the packaging of single dose injectable and single dose liquid preparations the strength should be stated as the total quantity of the active pharmaceutical substance per total volume (in each container) and per mL. If the volume in the container exceeds 1 mL, the concentration (quantity of active pharmaceutical substance per 1 mL) should be indicated immediately below the strength, either in brackets or in less prominent letters (where space allows). See example in figure 1. Preference for ampoule or vial container labelling is outlined in preference 11 below

Where space allows use different terminologies for strength as total quantity of active pharmaceutical per total volume (in each container) and total quantity of active pharmaceutical per mL. For example: ‘each 5 mL ampoule contains 100 mg (20mg/mL)’ or ‘100 mg in 5 mL (20 mg/mL)’.

3.2.3. Pharmac prefers on the packaging of multi-dose injectable products, such as insulin, the strength should be stated as strength per unit volume only, e.g. units/mL or mg/mL. Preference for ampoule or vial container labelling is outlined in preference 11 below

3.2.4. Pharmac prefers strength in total quantity of active pharmaceutical per total volume (in each container) or total quantity of active pharmaceutical per mL is displayed for injectable or single dose liquid preparations, even if other units of concentration such as percentages and ratios are displayed. See example in figure 1 and 2 below.

3.2.5. Pharmac prefers that for pharmaceuticals already established in New Zealand, that expression of salts, hydrates and solvents are represented on the label consistently with what is currently in the market for that pharmaceutical. For example “terlipressin” is depicted in product labelling and dosing is expressed as terlipressin acetate not the equivalent amount of terlipressin free base (1 mg of terlipressin acetate is equivalent to 0.85 mg of terlipressin). Pharmac recommends the NZULM be consulted in the first instance.

3.2.6. Pharmac prefers for multi-dose oral liquids (excluding controlled drugs) that the strength of liquid oral preparations should be stated as the total quantity of the active pharmaceutical substance per 5 mL volume (where appropriate). The concentration (quantity of the active pharmaceutical substance per one mL) should be indicated in less prominent letters.

3.2.7. Pharmac prefers for multi-dose controlled drug oral liquids, that the strength be expressed as the amount of the active pharmaceutical substance contained per mL.

Where possible strength should be depicted on labelling using the same unit of measure used when prescribed.

3.3. Pharmaceutical form

3.3.1. Pharmac prefers that pharmaceutical form be given due prominence and be included in all labelling and packaging components where the generic name and strength appears (where space allows).

3.3.2. Pharmac prefers that the formulation type be written in full on labelling(where space allows). For example, “Generic Name- Modified Release” instead of “Generic Name- MR”

3.4. Route(s) of administration

3.4.1. Pharmac prefers that positive messages be used to describe route of administration, such as “give by…”

3.4.2. Pharmac prefers, where space allows, a positive message precedes any negative statement. For example “For Infiltration, Nerve Block and Epidural Administration Only. Not for Intravenous Administration”

3.5. Specific warnings

New Zealand legislative requirements for certain pharmaceuticals may require that specific warnings essential for safe use are provided on the front face of the package and/or labelling. The Medsafe Label Statements Database, which provides a list of warning and advisory statements that are required on pharmaceuticals and related products, should be adhered to as required by section 13(1)(i) of the regulations.

3.5.1. Pharmac prefers specific warnings to be clearly identifiable from other information on labelling. For example the use of red font, or within a border to distinguish the warning from other information.

3.5.2. Pharmac prefers specific warning statements be included on both packaging and container labels (where space allows).

3.6. Storage conditions

3.6.1. Pharmac prefers that product specific storage conditions are easily distinguishable from other information on labelling, particularly when the pharmaceutical requires refrigeration. For example, with the use of bold font.

3.6.2. Pharmac prefers the use of positive statements to give direction. For example “For long term storage, store in a refrigerator at 2-8°C”.

4. Other information required by regulation

4.1. Pharmac prefers that mandatory information required on the labelling and/or packaging does not obscure the essential information as noted above. For example, the name and address of the manufacturer is mandatory but not essential for the safe selection/use of the pharmaceutical. Medsafe have provided a comprehensive guideline on the minimum requirements for labelling.

5. Error-prone abbreviations, symbol and dose designations

The use of abbreviations and acronyms may save time but can increase the potential for medication errors. The Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand (HQSC)’s error-prone abbreviations, symbols and dose designations should be considered when designing labelling.

5.1. Pharmac prefers that the HQSC-preferred term is used in labelling, where space allows.

6. Colour used in labelling

Colour can help correctly identify, classify, and differentiate between pharmaceuticals. However, relying totally on colour to do this can lead to mistakes. Additional graphic elements should be used to improve differentiation between pharmaceuticals.

6.1. Pharmac prefers written information to be written in colours that strongly contrast with its background.

6.2. Pharmac prefers that colour differences between strengths and presentations of a pharmaceutical are clearly distinguishable from one another. The same tone or hue should be avoided. This colour difference also needs to be clearly identifiable when the product is:

6.2.1. in isolation

6.2.2. in different lighting conditions

6.2.3. alongside other pharmaceuticals from the same manufacturer/supplier.

6.3. Pharmac prefers packaging and primary container colouring of a pharmaceutical to be consistent.

6.4. Pharmac prefers for tablet and capsule pharmaceuticals which are different colours between strengths within the manufacturer’s range (of that pharmaceutical form), that the colour of the physical tablet or capsule be reflected in the labelling of that strength.

Colours look different in different lighting conditions; people have different perceptions of colour; and colour blindness means some people see colours differently. There are a number of sources of best practice guidelines for colouring on packaging. The National Patient Safety Agency (England and Wales) had provided a series of useful design examples in its graphic design guidelines.

7. Expiry date

7.1. Pharmac prefers the expiry date to be clearly visible and where printed to be printed in indelible ink.

8. Space for a dispensing label and machine readable codes

8.1. For packaging designed to be used by the patient, Pharmac prefers a clearly designated space for affixing a patient label (where space allows).

8.2. Pharmac prefers that there are space allowances for machine readable codes and that the information contained within the machine readable code includes:

8.2.1. product information

8.2.2. batch number

8.2.3. expiry date

8.2.4. GTIN

Please note the Health Information Standards Authority (HISO) has endorsed the use of GS1 Standards for machine readable codes for pharmaceuticals(external link).

9. Blister containers

9.1. Pharmac prefers that every two blister pockets include the generic name, trade name (if any), pharmaceutical form and the strength of the pharmaceutical.

9.2. Where blisters are small, Pharmac prefers generic name, trade name (if any), pharmaceutical form and the strength of the pharmaceutical appear in repetitive diagonals.

9.3. Pharmac prefers that the expiry date and batch number appear at both ends or on the side of each blister.

10. Ampoule or vial containers

10.1. Pharmac prefers labelling on containers of single dose injectable preparations to have the strength appear prominently as total quantity of the active pharmaceutical substance per total volume in container. The concentration (quantity of active pharmaceutical substance per one mL) should be indicated immediately below the strength less prominently (where space allows). See example, figure 2, below.

10.2. Pharmac prefers that labelling on containers of multi-dose injectable products, such as insulin, express strength as strength per unit volume only, e.g. units/mL or mg/mL.

10.3. Pharmac prefers that labelling of ampoules and small vials to have information presented longitudinally along the length of the container.

10.4. Pharmac prefers where glass or clear plastic labelling is used key information needs to be clearly distinguishable. For example by inverting the text colour of this information to provide greater contrast.

11. Other considerations

Pharmac takes a pragmatic approach when considering a pharmaceutical for funding. Pharmac and its clinical advisors may have additional preferences not covered in this document and there may also be some instances where the stated preference is not appropriate for some pharmaceuticals.

Adapted from: Design for patient safety: A guide to the labelling and packaging of injectable medicines (National Patient Safety Agency, 2008).

Resources used in the development of these preferences

The following resources have been used in the development of the Pharmac labelling preferences and go into further detail on best practice:

- International Medication Safety Network. Position Statement Making Medicine Naming, Labelling and Packaging Safer.(external link)

- Medsafe New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. Guideline on the Regulation of Therapeutic Products in New Zealand Part 5 Labelling of medicines and related products. Edition 1.4 February 2015.(external link)

- Medsafe New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. Medicines Label Statements Databse.(external link)

- World Health Organisation. Essential medicines and health products, Guidance on INN(external link).

- World Health Organisation. Essential medicines and health products, Publications: Publishing INN Lists.

- New Zealand Universal List of Medicines.(external link)

- National Patient Safety Agency (England and Wales) Helen Hamlyn Research Centre. Design for patient safety: A guide to the graphic design of medication packaging. London (2007).

- National Patient Safety Agency (England and Wales) Helen Hamlyn Research Centre. Design for patient safety: A guide to the labelling and packaging of injectable medicines. London (2008).

- Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand. Tall Man Lettering, 31 January 2021.(external link)

- Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand. Error-prone abbreviations, symbols and dose designations, November 2021(external link).

- Supply Chain Standards. GS1 Standards – Health NZ | Te Whatu Ora, January 2024(external link)

- Best practice guideline on prescription medicine labelling (published by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration November 2005). TGA has since updated its labelling and packaging rules(external link)

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (UK). Best Practice Guidance On The Labelling and Packaging Of Medicines.(external link)

- Guideline on the readability of the labelling and package leaflet of medicinal products for human use (Revision 1 published by the European Commission 12 January 2009).(external link)

How we'll use these preferences

We have developed these labelling preferences following consultation with industry, regulators and the public, to reflect the naming and labelling preferences of Pharmac and its clinical advisers, when evaluating pharmaceuticals proposed for listing in the Schedule.

The preferences aim to provide guidance and transparency on Pharmac’s naming and labelling preferences. They address the most common naming and labelling issues that Pharmac encounters, and Pharmac’s preferred approach.

These preferences are separate from requirements set out in legislation and regulations. We’re confident they are consistent with regulatory requirements. But if inconsistencies arise, then regulatory and legislative requirements (including those that might occur in future) take precedence. Regulatory requirements are set out in the Medicines Act 1981, the Medicines Regulations 1984, and Labelling of medicines and related products.

Medsafe's guideline for labelling medicines – Medsafe website(external link)

How these preferences will fit into Pharmac decision making

The naming and labelling preferences are voluntary, and Pharmac will use these preferences within the context of its wider decision making framework when considering medicines for listing in the Pharmaceutical Schedule. That framework is based on Pharmac pursuing its statutory objective(external link) which is “to secure for eligible people in need of pharmaceuticals, the best health outcomes that are reasonably achievable from pharmaceutical treatment and from within the amount of funding provided”1.

To achieve this objective, Pharmac will be guided by Factors for Consideration2 set out in Pharmac’s Operating Policies and Procedures (OPPs). These are published on Pharmac’s website.

The labelling preferences will be considered when Pharmac applies Factors for Consideration, where labelling may be relevant within each evaluation process. For example, this may include those Factors for Consideration which relate to suitability.

In our decision-making, when applying the Factors for Consideration, the evaluation of products will take into account considerations outlined in the Annual Invitation to Tender or other procurement documents.

Pharmac will continue to consider naming and labelling alongside all other relevant considerations, for example cost benefits, health needs, securing supply, and benefits associated with harmonisation with other jurisdictions.

Pharmac does not intend to apply these preferences retrospectively to products that are currently listed. However, should currently listed products be re-evaluated, for example following a new procurement process, the preferences will apply.

Definitions

The definitions of container and package in these preferences are consistent with definitions in the Medicines Act 1981. A medicine can have only one container. Bottles, tubes, ampoules, sachets and blisters are examples of containers. A container may be enclosed in a package, and there may be multiple layers of packaging. Cardboard boxes are a common form of package used for medicines.

1 Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act 2022